Hey there! I’m on the lookout for my next engineering leadership adventure. If you know of any roles let me know through my contact page or on LinkedIn.

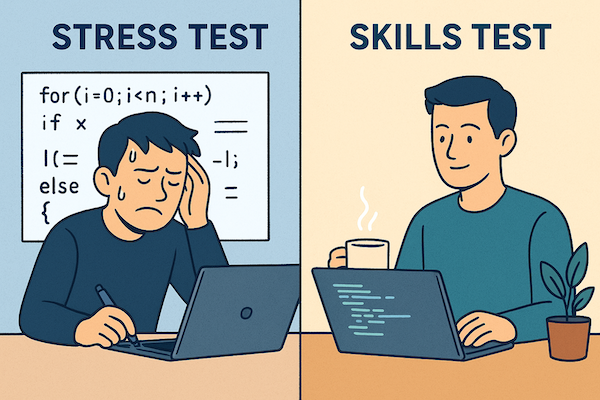

From Stress Test to Skills Test: A Smarter Approach to Technical Interviews

20 minutes. That’s how long I sat staring at a blank page while the interviewer waited, patiently observing. 20 minutes of considering the different possibilities; 20 minutes of talking myself down from panic; 20 minutes of painful inactivity. The longer I took the more I worried about what my interviewer was thinking. I finally gave up trying to figure out the perfect solution and just started coding something. The mental blocks shattered, and everything began to fall into place.

20 minutes. That’s how long I sat patiently waiting for her to start solving the challenge. 20 minutes of wondering if I needed to give her a hint; 20 minutes of watching her try to calm down; 20 minutes of me trying to stay engaged. The longer she took, the more I worried this was a waste of both of our time. She finally gave up, and in tears stopped the interview.

These two moments — separated by perspective, but still similar — underscored for me that the problem wasn’t just with the candidates. It was with the interview process itself.

There had to be a better way.

The Purpose of the Coding Interview

Coding assessments have become notorious in our industry for presenting problems you would never face in everyday work, conducted by interviewers more focused on intellectual sparring than genuine evaluation, and take-home challenges you spend your weekend working on only to receive a curt followup email thanking you for your time, but they’ve already filled the position. They are intense and stressful, they vary from company to company, and they don’t seem to achieve their stated goal.

Even so, they aren’t without merit.

There are two reasons for the coding interview: to filter out the unqualified, and to see how candidates think and work. The question is, “Do traditional technical interviews address these two reasons?” I argue that they do not.

Where the Traditional Coding Interview Falls Short

First, consider the reason to filter out the unqualified. Yes, you want to eliminate candidates who lack the competency for the role, but you don’t want to eliminate those who are competent, but who don’t perform well under high-pressure and time-constrained situations.

Consider these findings from Microsoft:

The impact on performance was drastic: nearly twice as many participants failed to solve the problem correctly, and the median correctness score was cut more than half, when simply being watched by an interviewer.

This means traditional interviews can systematically misrepresent candidate ability. The results for women were even worse:

In the public setting, no women (n = 5) successfully solved their task; however, in the private setting, all women (n = 4) successfully solved their task—even providing the most optimal solution in two cases.

Second, I remain unconvinced that testing candidates’ abilities to solve LeetCode challenges, (easy or hard,) shows anything beyond a person’s ability to memorize challenges and handle high-stress, test-taking scenarios. Homegrown challenges are often equally unfruitful. When hiring, I’m looking for a candidate’s ability to assess trade-offs, that they understand best practices, that they produce quality code, and have a good philosophy of software design. Traditional technical interviews don’t address these concerns.

A Turning Point

The turning point for me came after reading an article about replacing the technical challenge with code reviews. In this scenario, the interview transforms from a challenge to a conversation, wherein the candidate is required to evaluate the code, explain what it does, and provide feedback about how it might be improved. This style is effective because it reduces the anxiety of the challenge, reveals problem-solving approaches in a realistic context, and mirrors the kinds of technical conversations they would have on the job.

After using this on a handful of interviews, however, I found it fell short in two areas: 1) reading code isn’t the same as writing code; 2) you don’t get to see how the candidate works. This led me to come up with, what I believe is a better solution.

A Better Way

I finally settled on the following solution:

- Provide at least one file and associated tests from existing production code (these are run from the interviewing environment, not in production)

- Modify the code and tests to introduce bugs or inefficiencies as desired and remove features you want the candidate to add

- Provide a prompt to fix any failing tests, add a new function/method to do x, and perform any refactorings on the file or tests that make sense.

An example prompt might look like the following:

The

/ui/versionendpoint, represented in theapp.jsfile, is used by the AcmeApp to ensure the version used by the backend matches the version running on the client’s machine. Each time the UI is deployed, it uses the API to set the version in the database.Because this endpoint has been around since the beginning of AcmeApp, it has gone through several iterations. The current version is a bit of a mess, and we would like to refactor it.

It has three endpoints:

GET /ui/version- returns the current versionPOST /ui/version- sets the current versionDELETE /ui/version- deletes the current versionThings to note:

There should only ever be one version in the database.

What we need you to do:

- Refactor the code to make it more readable, maintainable, and modern.

- Add tests to ensure the code works as expected

- Some initial tests have been written, but more may be needed

- Fix any bugs you find

- Identify security issues, if any

Files

main.js- the test fileapp.js- the actual app file— Don’t modify these files —

support/semver.js- simplified version of the semver librarysupport/db.js- a fake database.support/http.js- a dumbed down HTTP mocking library for the response object

Why it’s Better

What follows are just some of the reasons why performing technical interviews this way is better:

See how candidates work in a realistic setting

One of the reasons this is a better solution to the technical interview is that it better reflects a day-in-the-life of what candidates will do: reading code, fixing bugs, adding features, writing tests, and reading product requirements. By using this method, you get insight into how the candidate works and at what level.

- Do they use tests to validate their code?

- Do they even run the tests? (Don’t get me started)

- What’s important to them when refactoring?

- An inexperienced engineer might waste time reformatting a file to fit their preferences while more experienced engineers will focus on efficiencies, good naming, and design.

- Do they follow instructions or make assumptions?

- There have been many instances where candidates change files they were explicitly told not to modify.

- Can they do the work, and at what level?

Avoid the blank-page problem

One of the biggest problems with traditional coding challenges is facing the blank editor. How should I start this? How should I organize it? What’s the right solution? You can imagine a dozen different ways to solve it, but you’re not sure which way is optimal. When you are given an existing page of code, on the other hand, you’re able to focus on what the code is currently doing, and sidestep some of the anxiety brought on by facing the Paradox of Choice.

Encourages a two-way technical discussion

The whole point of the interview process is to determine if a candidate is a good fit for your team: Are they qualified? Are they a good culture fit? Are they better than the rest of the candidates? Portions of these questions will be answered in other interviews, but additional information can be provided in the technical interview as well. As the candidate “solves” the challenge, it’s important to keep dialogue open to understand why they’re making the choices they are:

- Why was it important to do x or y?

- Did you consider x?

- Why did you break out that block into a new function?

- Why did you make that a private method?

- Is that change optimal? Why? Is it important that it is?

These are just a few of the many types of questions you can ask during the process, the purpose of which is to better understand why the make the choices they do, the trade-offs they consider, and if this is someone you or your team would want to work with.

Adjusts for your company and your project

As stated, this type of technical interview should use code from an existing production code base. This allows your interviews to be specific to your company and project. By doing it this way it allows you to see if candidates have the background and experience to perform the role to which they are applying. For example, a database company might use a challenge that only those who have worked with database would be able to answer. Likewise, companies focused on AI, web applications, search, or anything else could tailor the challenge for their specific industry, and not settle for a cookie-cutter coding challenge.

An Imperfect Solution

There isn’t a perfect technical interview. Candidates’ anxiety will still run higher than in Q&A style interviews, interviewers will still occasionally be detached or condescending, and the wrong candidate will still get through when the better one gets left behind. We can’t attain perfect, but we can and should improve our process so we can get closer.

Traditional interviews fall short in helping candidates overcome anxiety and accurately measuring competence and cultural fit. Attempts have been made to improve technical interviews with take-home challenges, code review interviews, and Bug Squash interviews. Each iteration has made improvements, but have also introduced other problems.

The solution presented in this article seeks to address the issues in the traditional coding interview as well as the problems in other types as well. It affords the candidate the opportunity to show how they would work against a real-world problem, provides greater opportunities for interviewers to ask questions and get a feel for culture fit, it helps alleviate anxiety by starting candidates off with existing code, and it can be adjusted for any company and project.

It may not be perfect, but it’s a proven step toward more accurate, fair, and effective hiring — and worth serious consideration by any team that wants to improve the quality of its hires.